Chapter 4: The Beginning and Middle of a Consultation

In Chapters 4 and 5, you’ll explore practical strategies for navigating the three key stages of a Writing Center consultation: the beginning, the middle, and the end.

While these stages are shaped by real-time interaction in face-to-face and video consultations, asynchronous consultations unfold differently—there’s no live conversation. That said, many of the strategies for guiding students through the middle of an appointment are applicable across all appointment formats.

Beginning a Consultation

Consultants from the University of Wyoming Writing Center share their advice for starting strong.

Setting the Right Tone From the Start

Written by Gregory B., University of Wyoming Writing Center consultant

“When greeting a client, especially as a new consultant, it is important to set the right tone. I like to dedicate the first five minutes of any appointment to welcoming the client to the Writing Center, asking how they are doing, and beginning to discern the reason they have made an appointment. Usually, I start with questions such as “How is your week going?” or “Are you enjoying this class?”. Then I ask about the assignment they have brought in and the class for which they have been assigned that work. Usually this naturally segues into asking about the specific type of help they are looking for. Once we have organized our thoughts, I tend to try one of two approaches. If the client really wants help with a specific thing like MLA or APA citations, I will dedicate the first portion of the consultation to that, jumping around the essay as needed. Alternatively, if my client feels that they need more general help or are unsure of how to begin, I just start at the top of the essay (or wherever they left off in cases of longer writing) and begin to read aloud. By reading the essay aloud myself, I situate both of us as reading and listening to the content and structure. I then read about a paragraph and look for any errors in structure, syntax, et cetera. Then, gauging the client’s response, I begin to provide feedback and clarify with them about how their goals for the writing line up with what is on the page. Usually, at this point the client is invested in the process and ready to collaborate in their learning. By dedicating a little time to understanding the assignment before we begin work, I allow myself the space to actually interpret the client’s perspective on the writing and create concrete goals for the rest of the session. Often, we feel we must immediately begin the consultation. However, if the client is uncomfortable, then no true work will get done. Instead of ‘wasting’ the first five minutes, we have now wasted an entire consultation. Don’t be afraid of getting to know your client and their assignment. Understanding the broader context is crucial to having a successful appointment and is not to be miscounted.”

What If You Have Imposter Syndrome?

Written by Erin B., University of Wyoming Writing Center consultant

“You won’t be an expert in every type of writing no matter how long you work in the Writing Center, but that doesn’t mean that you don’t have good advice to offer for any genre. There are tenants of writing that are always applicable (grammar, flow, readability, logical structure), and having those touchstones will help you stay confident even when you find yourself in the unknown. Outside of that, don’t be afraid to ask your clients if there are specific guidelines for their project. If the student doesn’t know, look it up—even in the middle of the consultation! If you have a few minutes before your consultation, search online and take notes on specific tips/tricks/content/structure that you can have with you in the meeting. A few minutes of prep (if you have time for it) before the meeting will make you feel more confident about what you’re saying, and asking questions of your client can help you move forward confidently!”

Is Your Client Combative or Just Vulnerable?

Written by Gregory B., University of Wyoming Writing Center consultant

“Often, as a writing center consultant, it is easy to forget the experience of having your own writing analyzed. After working in the writing center for multiple years, I was asked to help provide mock consultations to new staff. While working with my consultant, I found myself bristling at the idea of changing anything and found some of her feedback to be pushing back against my preconceived notions of the level of my writing. This gave me an overwhelming sympathy for the clients I have worked with. Writing is a very personal and intimate expression of a person’s ideas, feelings, and understandings. When we as writing center consultants critique that writing, it can feel like an attack on the writer rather than a comment on their writing efficacy. Because of this, it is crucial for us as consultants to be mindful of the delivery of our feedback. Sometimes, if a client appears discouraged, it is helpful to point out something positive that they accomplished. When providing a critique, it is also important to choose positive language and focus on how something can be improved rather than how it is wrong. For example, if your consultant struggles with using incorrect verbs to describe certain actions, you may not want to say “This word doesn’t mean what you think it does. You need this word” because that comes across as combative. Instead, asking them what they mean by a word allows you to understand their intention without delegitimizing their work.”

Building Rapport With Your Client

Written by Erin B., University of Wyoming Writing Center consultant

“Building a rapport with clients can be tricky, and no one has a track record of 100% stellar, meaningful, fun consultations. That said, there are a few things that always help get your consultation onto the right track and moving forward. Start with basic intro questions: How are you today? How’s writing going? What are you working on? With these baseline questions established, you can gather a couple of important pieces of information, including how they currently feel about what they’re writing. This is the most important foundation to start building rapport. If you understand how they feel about writing, then you can sympathize with their frustrations, be excited about their progress, empathize with difficult topics or assignments, and validate how they feel about where they are with their piece. People want to know that you aren’t judging them for their writing or where they are struggling, so relating to them through stories of similar experiences with difficult writing or assignments is important. I also find that not taking myself too seriously gets clients to open up faster—making small jokes, being energetic and interested in the topics that they bring, encouraging them to come back, and complimenting them on the things that they do well will make students seek you out again. If making jokes is not your style, that’s fine! What really matters is that your client know without a doubt that you care about them and their success.”

The Middle of a Consultation

The middle of a consultation is where the bulk of the work happens (aim for 35-40 minutes in a 50-minute consultation), but it can also be the trickiest part to navigate. How do you offer feedback that’s both clear and empowering? How do you strike the balance between being directive enough to be helpful, without entirely taking over the client’s writing?

This chapter introduces the difference between direct and indirect consulting styles, showing how word choices can shape a writer’s understanding of what to revise, and how. You’ll see examples of both helpful and less effective feedback, learn strategies to avoid overwhelming your client, and practice phrasing comments in a way that is actionable and still respectful of the writer’s voice. While the illustrative screenshots in this chapter are taken from asynchronous ‘Review and Return’ appointments, the advice translates to in-person and video appointments.

Direct vs Indirect Tutoring Styles

Written by Francesca King, Director, University of Wyoming Writing Center

To write this chapter, I looked at Writing Center consultant feedback to identify both strong examples of instructional comments and some potentially problematic ones. I analyzed language structures and found that while certain comments may feel clear to the consultant, they can be ambiguous when it comes to identifying the actual writing issue, or explaining how the student should address it.

The least clear comments I found tended to use indirect speech acts that sound like suggestions. In contrast, direct speech acts—which function as explanations, assertions, commands, or questions—tend to be much clearer for students to interpret.

Direct speech acts are relatively easy to spot. Declarative statements offer information (e.g., “Essay titles are capitalized.”), imperative statements tell the writer what to do (e.g., “Add a period here.”), and interrogative statements pose a question (e.g., “What does photosynthesis mean?”).

When writing feedback for my English 1010 or Technical Writing classes, I’ll often combine these. For example: “What does photosynthesis mean? Write a one-sentence definition here.” Or in reverse: “These two paragraphs need a stronger transition. What transition words would create that bridge or connection between the two?”

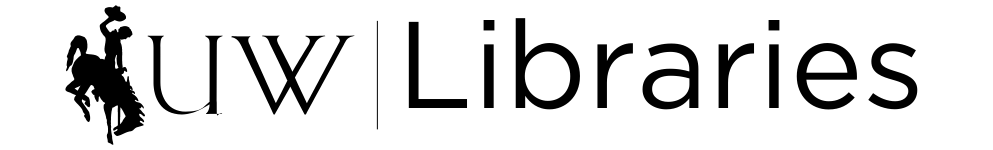

Here, Banaz uses a declarative statement to explain what a summary statement is and how it functions in a resume. She then follows with semi-imperative statements, phrased using ‘you could’ sentences that suggest she’s navigating the fine line between offering suggestions and being too aggressively directive. Banaz has also attached example resumes to support her suggestions with models.

Indirect Speech Acts

In contrast to Banaz’s feedback, more traditionally indirect speech acts—like the ones below—can lead to mixed messages and communicative misfires. For example, a phrase like “Do you really want to say that?” might feel like a helpful nudge to the consultant, but can leave the student unclear on the actual revision being asked of them. Indirect speech acts can also take forms like “You might consider…” or “You might want to change…” These can confuse students because the phrasing suggests that revision is optional. The form and function of these comments don’t align, as they are not genuine questions using “how” or “wh-” words—they only appear to be.

I have pulled four examples of indirect speech acts from W.C. consultant feedback. In brackets, I’ve provided one possible meaning that the consultant intended to convey.

1. Do you have a page number for this citation?

[Page numbers are generally used in MLA in-text citations; for example (Smith 163). Delete ‘paragraph 3’ and replace with the page number. If your source does not use page numbers, do not include anything after the parenthetical citation: (Smith)].

2. Do you think you could maybe paraphrase these findings? I’m thinking it might sound a little more natural and flow a little better.

[You have three quotes from three different authors in this short paragraph. To avoid disrupting the flow of your writing with lots of quotation marks, try paraphrasing this paragraph (rewriting the author’s words in your own words). Click here for a W.C. handout on paraphrasing, and how it differs from summary and direct quotation.]

3. Can you tell your reader a bit more about how you arrived at the idea of nostalgia?

[Tell your reader more about how nostalgia relates to your topic sentence.]

4. Perhaps you could put in a transition phrase like “In a different way,” or something that helps shift your reader’s focus a little more?

[Use a transition phrase here (for example, ‘In a different way’) to signal to your reader that you’re moving on to another thought or idea.]

These comments were intended as directives, but because they communicated their ‘commands’ indirectly, students considered them to be suggestions at best, and disregarded them.

We tend to gravitate towards indirection for two reasons

- Politeness (worries about exploiting, or drawing attention, to power dynamic)

- Reluctance to give a specific answer (worries about being too prescriptive or directive).

Being polite, and acknowledging the student’s authorial ownership are important considerations, but instructors need to incorporate more direct and explicit feedback, if students are to receive proper help.

Avoiding Other Ways of Being Vague

There are other ways of being vague that, in context, might confuse student writers at any level. In her book The Online Writing Conference (2010) Beth Hewett describes how she once used a highlighter tool to indicate a place in a sentence where a student needed to make an edit. The student, a non-native English speaker and ELL, had written “An scientific article…” Hewett highlighted “An scientific”, assuming the student would immediately recognize the article error (cite).

Instead, the student revised by deleting “An scientific” entirely, beginning the sentence nonsensically with the capitalized word “Article.” Hewett’s use of the highlighter tool functioned as a hint, not a clear instruction. Because even small, seemingly obvious errors can lead to incorrect revisions, students benefit from whole-class instruction on how to interpret highlighted words or phrases.

Of course, it can be exhausting—or even impossible—to offer whole-class instruction for every single error.

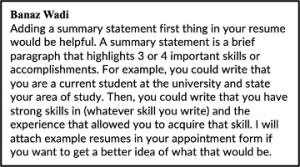

Emily is using a technique in her asynchronous feedback which explains to her client, Hanna, how she will address the specific points which Hanna submitted in the pre-appointment form (in this case, grammar and conciseness). Written feedback can be difficult to navigate with lots of track changes and margin comments, so Emily is hoping that by highlighting phrases in yellow, it will draw Hanna’s attention to grammar or phrasing concerns. Highlighting phrases in blue will draw Hanna’s attention to phrases that Emily thinks can be cut for conciseness. Note that Emily is just suggesting these changes, to allow Hanna to retain authorial ownership. Time permitting, Emily will also add margin notes to the highlighted phrases to allow Hanna to benefit from a written explanation.

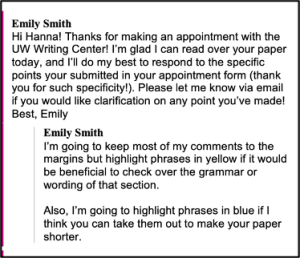

In the above example, this student is a repeat client, so Makayla is using blue highlighting to mark places where she can see clear improvement from previous weeks. Explaining this upfront again helps the student understand how to interpret a tutor’s comments.

Examples of Helpful Comments

It’s essential to use vocabulary that clearly conveys writing conventions, instructional expectations, and how students can address both. If we accidentally write unhelpful comments, we fail to help them to revise, in part because we fail to specify through our vocabulary what is in need of revision, and how to revise it.

These are recent examples of graduate and undergraduate consultants providing precise, clear, and accurate suggestions for revision.

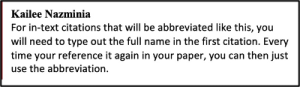

Kailee is providing a simple lesson about APA citations.

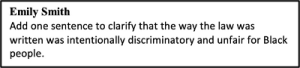

Emily is providing a specific revision suggestion, using an imperative statement.

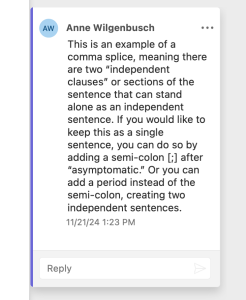

Anne is giving a short, accessible lesson on comma splices.

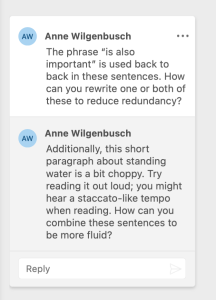

Anne is suggesting ways for a native English speaker to hear the ‘choppiness’ in their writing without getting into the weeds of difficult grammar lessons.

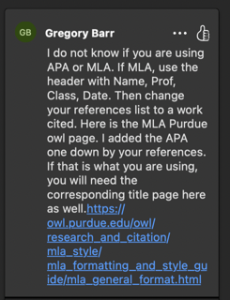

Gregory is sending a direct link to Purdue OWL to assist his asynchronous client with citations.

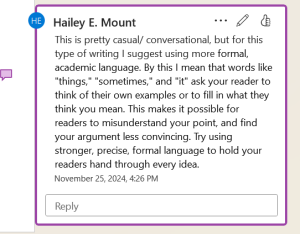

Hailey is advising her client to use more precise language to leave no room for reader error.

Avoiding Saturating The Client

Written by Francesca King, Director, University of Wyoming Writing Center

When was the last time you felt complete brain saturation? Perhaps it was Intro to Chem, or in another particularly uncomfortable class. For me, it’s been a long while since I was forced to rapidly learn something outside of my comfort zone, but after 10 years, I’ve picked up my violin again and started taking lessons.

My teacher has a lot of suggestions for me to improve my hand posture, bowing style, shifting technique, double-stops… you name it, I could do it better. He tells me the difference between martele, spiccato, and detache bow strokes, and how to achieve each effect. But as this is all new information to me, my brain feels completely saturated after about 25 minutes.

Focusing too much on theory while trying to play was actually making my technique worse. I explained how I was feeling to my teacher, and we stripped things back to basics. He told me to concentrate just on relaxing my shoulders and thumbs—one manageable thing to focus on. That one change improved my posture, which in turn improved my wrist flexibility, which improved my bow strokes and my overall tone.

This was a good reminder for me of what it feels like to be a beginner, and how overwhelming it can be to receive too much feedback at once. As consultants, we’re often tempted to correct everything we see, but writers (especially less confident ones) can’t take it all in. Focusing on one clear revision priority not only keeps the session manageable, but often leads to improvements in other areas.

During the middle of the consultation, when you’re identifying what to prioritize, keep this in mind. Here are some strategies that help writers make meaningful progress without feeling overloaded:

- Acknowledge 1–2 genuine strengths in the draft to build trust and confidence.

- Choose a single higher-order concern (like focus, clarity, or organization) to explore together.

- Frame your feedback as a conversation: ask questions, model options, and gauge how the writer is responding.

- If it’s appropriate, introduce a small teachable concept—something the client can try out in real time.

Media Attributions

- Banaz feedback

- Emily Feedback

- Makayla feedback

- Kailee feedback

- Emily 2 feedback

- Anne feedback

- Anne 2 feedback

- Gregory feedback

- Hailey feedback