4.23 Evidence-Based Practice and Research

Ernstmeyer & Christman - Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

There are many ties between safe, quality client-centered care; evidence-based practice; research; and quality improvement. These concepts fall under the umbrella term “scholarly inquiry.” All nurses should be involved in scholarly inquiry related to their nursing practice, no matter what agency they work for. The American Nursing Association (ANA) Standard of Professional Performance called Scholarly Inquiry lists competencies related to incorporating evidence-based practice and research for all nurses. See the following box for a list of these competencies.[1]

Competencies of ANA’s Scholarly Inquiry Standard of Professional Performance[2]

- Identifies questions in the health care or practice setting that can be answered by scholarly inquiry.

- Uses current evidence-based knowledge, combined with clinical expertise and health care consumer values and preferences, to guide practice in all settings.

- Participates in the formulation of evidence-based practice.

- Uses evidence to expand knowledge, skills, abilities, and judgement; to enhance role performance; and to increase knowledge of professional issues for themselves and others.

- Shares peer-reviewed, evidence-based findings with colleagues to integrate knowledge into nursing practice.

- Incorporates evidence and nursing research when initiating changes and improving quality in nursing practice.

- Articulates the value of research and scholarly inquiry and their application to one’s practice and health care setting.

- Promotes ethical principles of research in practice and the health care setting.

- Reviews nursing research for application in practice and the health care setting.

Reflective Questions

- What Scholarly Inquiry competencies have you already demonstrated during your nursing education?

- What Scholarly Inquiry competencies are you most interested in mastering?

- What questions do you have about the ANA’s Scholarly Inquiry competencies?

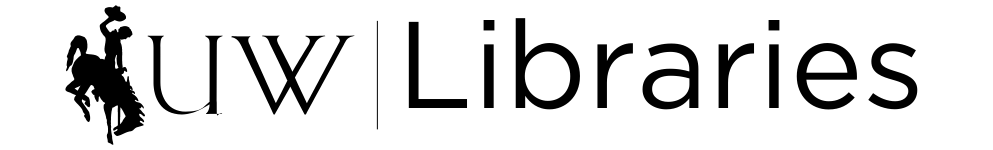

Nursing practice should be based on solid evidence that guides care and ensures quality. Evidence-based practice (EBP) is the foundation for providing effective and efficient health care that promotes improved client outcomes. Evidence-based practice is defined by the American Nurses Association as, “A lifelong problem-solving approach that integrates the best evidence from well-designed research studies and evidence-based theories; clinical expertise and evidence from assessment of the health care consumer’s history and condition, as well as health care resources; and client, family, group, community, and population preferences and values.”[3] See Figure 9.7[4] for an illustration of evidence-based practice.

Evidence-based practice is the foundation nurses rely on to ensure their interventions, policies, and procedures are based on data supporting positive client outcomes. EBP relies on scholarly research that generates new nursing knowledge, as well as quality improvement processes that review client outcomes resulting from current nursing practice, to continually improve quality care. EBP encourages health care team members to incorporate new research findings into their practice, referred to as translating evidence into practice. Nurses must recognize the partnership between EBP and research; EBP cannot exist without continual scholarly research, and research requires nurses to evaluate research findings and incorporate them into their practice.[5]

Read examples of nursing evidence-based projects from Johns Hopkins.

Newly graduated nurses may become immediately involved with evidence-based practice and quality improvement processes. The Quality and Safety Education (QSEN) project further elaborates on evidence-based practice for entry-level nurses with the definition of EBP as, “integrating best current evidence with clinical expertise and client/family preferences and values for delivery of optimal health care.” See Table 9.4 for the knowledge, skills, and attitudes associated with the QSEN competency of evidence-based practice for entry-level nurses.

Table 9.4. QSEN: Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes Associated With Evidence-Based Practice

| Knowledge | Skills | Attitudes |

|---|---|---|

| Demonstrate knowledge of basic scientific methods and processes.

Describe EBP to include the components of research evidence, clinical expertise, and client/family values. |

Participate effectively in appropriate data collection and other research activities.

Adhere to Institutional Review Board (IRB) guidelines. Base individualized care plan on client values, clinical expertise, and evidence. |

Appreciate strengths and weaknesses of scientific bases for practice.

Value the need for ethical conduct of research and quality improvement. Value the concept of EBP as integral to determining best clinical practice. |

| Differentiate clinical opinion from research and evidence summaries.

Describe reliable sources for locating evidence reports and clinical practice guidelines. |

Read original research and evidence reports related to area of practice.

Locate evidence reports related to clinical practice topics and guidelines. |

Appreciate the importance of regularly reading relevant professional journals. |

| Explain the role of evidence in determining best clinical practice.

Describe how the strength and relevance of available evidence influences the choice of interventions in provision of client-centered care. |

Participate in structuring the work environment to facilitate integration of new evidence into standards of practice.

Question rationale for routine approaches to care that result in less-than-desired outcomes or adverse events. |

Value the need for continuous improvement in clinical practice based on new knowledge. |

| Discriminate between valid and invalid reasons for modifying evidence-based clinical practice based on clinical expertise or client/family preferences. | Consult with clinical experts before deciding to deviate from evidence-based protocols. | Acknowledge own limitations in knowledge and clinical expertise before determining when to deviate from evidence-based best practices. |

Reflective Questions: Read through the knowledge, skills, and attitudes in Table 9.4.

- How are you currently integrating evidence-based practice when providing client care?

- Where do you find information on current evidence-based practice?

- Have you witnessed any routine approaches to care that resulted in less-than-desired outcomes or adverse events?

- What else would you like to learn about evidence-based nursing practice?

Keeping Current on Evidence-Based Practices

Health care is constantly evolving with new technologies and new evidence-based practices. Nurses must dedicate themselves to being lifelong learners. After graduating from nursing school, it is important to remain current on evidence-based practices. Many employers subscribe to electronic evidence-based clinical tools that nurses and other health care team members can access at the bedside. Nurses also independently stay up-to-date on current evidence-based practice by reading nursing journals; attending national, state, and local nursing conferences; and completing continuing education courses. See the box below for examples of ways to remain current on evidence-based practices.

Examples of Evidence-Based Clinical Supports, Nursing Journals, and Conferences

American Nurse (published by the American Nurses Association)

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality – EPC Evidence-Based Reports

Turning Research Into Practice (TRIP) Database

American Nursing Association – Events and Continuing Education

Research

Earlier in this chapter we discussed the process of quality improvement and the manner in which it is used to evaluate current nursing practice by determining where gaps exist and what improvements can be made. Nursing research is a different process than QI. The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines nursing research as, “Systematic inquiry designed to develop knowledge about issues of importance to the nursing professions.”[6] The purpose of nursing research is to advance nursing practice through the discovery of new information. It is also used to provide scholarly evidence regarding improved client outcomes resulting from evidence-based nursing interventions.

Nursing research is guided by a systematic, scientific approach. Research consists of reviewing current literature for recurring themes and evidence, defining terms and current concepts, defining the population of interest for the research study, developing or identifying tools for collecting data, collecting and analyzing the data, and making recommendations for nursing practice. As you can see, the scholarly process of nursing research is more complex than the Plan, Do, Study, Act process of QI and typically requires more time and resources to complete.[7]

Nurse researchers often use the PICOT format to organize the overall goals of the research project. The PICOT mnemonic assists nurses in answering the clinical question to be studied.[8] See Figure 9.8[9] for an image of PICOT. PICOT terms are further defined in the following box.

PICOT

P: Population/Problem: Who are the clients that will be studied (e.g., age, race, gender, disease, or health status, etc.) and what problem is being addressed (e.g., mortality, morbidity, compliance, satisfaction, etc.)?

I: Intervention: What is the specific intervention to be implemented with the research population (e.g., therapy, education, medication, etc.)?

C: Comparison: What is the alternative intervention that will be used to compare to the treatment intervention (e.g., placebo, no intervention, different medication, etc.)?

O: Outcome: What will be measured and how will it be measured and with what identified goal (e.g., fewer symptoms, increased satisfaction, reduced mortality, etc.)?

T: Time Frame: How long will the interventions be implemented and data collected for this research?

After the researcher has completed the PICOT question, these additional questions should also be considered to protect clients’ rights and reduce the potential for ethical conflicts:

- Was the study approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB)? The IRB, also known as an independent ethics committee, reviews research studies to protect the rights and welfare of participants.[10] Read more about ethics related to research in the “Ethical Practice” chapter.

- Were the participants protected? Researchers have the responsibility to protect human rights, uphold HIPAA, and respect the personal values of the participants.

- Did the benefits of the intervention outweigh the risk(s)? Researchers have the responsibility to identify if there is a possibility for increased harm to the clients because of the research project.

- Were informed consents obtained? All research participants must provide written informed consent before a study can begin. Researchers must ensure the participants were fully informed of the study, provided risks and benefits, and allowed to exit the study at any time.

- Were vulnerable populations protected? Populations of study that include infants, minorities, children, elderly, socioeconomically disadvantaged, prisoners, etc., are considered vulnerable populations, and researchers must ensure their rights and safety are accounted for.

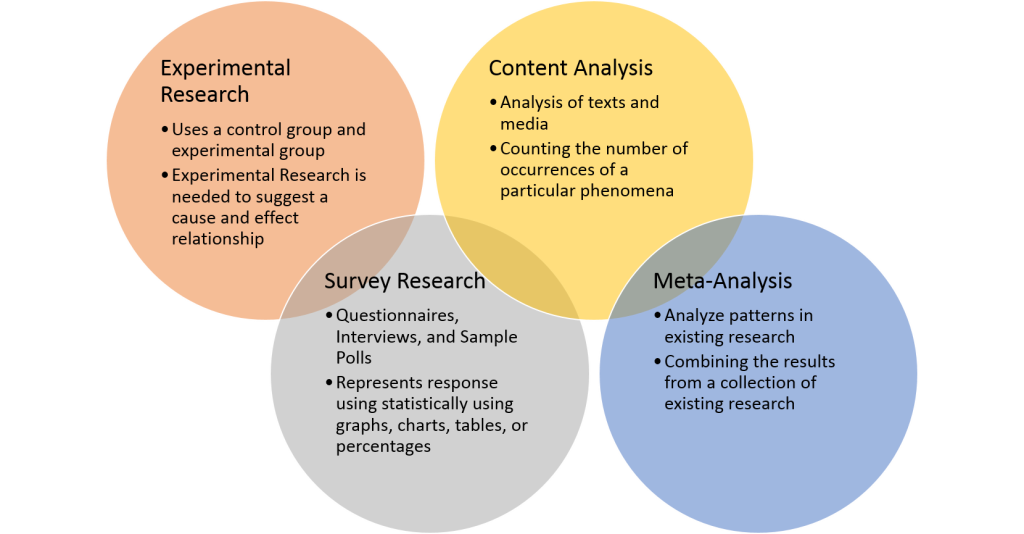

After the nurse researcher confirms participants’ rights are protected and has established a PICOT question, the next step is to design the research study and review existing research. Research designs are categorized by the type of data that is collected and reviewed. See Figure 9.9[11] for an illustration of different types of research. The three basic types of nursing research are quantitative studies, qualitative studies, and meta-analyses. See definitions and examples of these types in the following box.

Types of Research

- Quantitative Studies: These studies provide objective data by using number values to explain outcomes. Researchers can use statistical analysis to determine the strength of the findings, as well as identify correlations.

View an example of an quantitative research study.

- Qualitative Studies: These studies provide subjective data, often focusing on the perception or experience of the participants. Data is collected through observations and open-ended questions and is often referred to as experimental data. Data is interpreted by recurring themes in participants’ views and observations.

View an example of a qualitative research study.

- Meta-Analyses: A meta-analysis, also referred to as a “systematic review,” compares the results of independent research studies asking similar research questions. A meta-analysis often collects both quantitative and qualitative data to provide a well-rounded evaluation by providing both objective and subjective outcomes. This research design often requires more time and resources, but it also promotes consistency and reliability through the identification of common themes.

View an example of a meta-analysis/systematic review.

Nurses must understand the types of research designs to accurately understand and apply the research findings. Additionally, only research from peer-reviewed scholarly journals should be used. Scholarly journals use a process called “peer review” to ensure high quality. An article that is peer reviewed has been reviewed independently by at least two other academic experts in the same field as the author(s) to ensure accuracy.

Nurses must also be aware of the difference between primary and secondary sources of scholarly evidence. A primary source is the original study or report of an experiment or clinical problem. The evidence is typically written and published by the individual(s) conducting the research and includes a literature review, description of the research design, statistical analysis of the data, and discussion regarding the implications of the results.

A secondary source is written by an author who gathers existing data provided from research completed by another individual. A secondary source analyzes and reports on findings from other research projects and may interpret findings or draw conclusions. In nursing research secondary sources of evidence are typically published as a systematic review and meta-analysis.

View QUT Library’s Primary vs. secondary sources YouTube video.[12]

By understanding these basic research concepts, nurses can accurately implement current evidence-based practice based on continually evolving nursing research.

Next: 4.24 Spotlight Application

Media Attributions

- Flowchart-sm

- PICOT by Kim Ernstmeyer PNG

- Quantitative_methods

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- “Flowchart-sm.png” by Bates98 is licensed under CC BY_SA 4.0 ↵

- Chien, L. Y. (2019). Evidence-based practice and nursing research. The Journal of Nursing Research: JNR, 27(4), e29. https://doi.org/10.1097/jnr.0000000000000346 ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2006). Nursing research. https://www.aacnnursing.org/News-Information/Position-Statements-White-Papers/Nursing-Research ↵

- Lansing Community College Library. (2025). Nursing: PICOT. https://libguides.lcc.edu/c.php?g=167860&p=6198388 ↵

- “PICOT.png” by Kim Ernstmeyer for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- U. S. Food & Drug Administration. (2025). Institutional review boards frequently asked questions: Guidance for institutional review boards and clinical investigators. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/institutional-review-boards-frequently-asked-questions ↵

- “Quantitative_methods.png” by Remydiligent1 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- QUT Library. (2020, November 22). Primary vs. secondary sources [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/FZRxYfWYEBI ↵

References

AHRQ. (2015, July). TeamSTEPPS: National implementation research/evidence base. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/evidence-base/safety-culture-improvement.html

AHRQ. (2020, January). Pocket guide: TeamSTEPPS. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/essentials/pocketguide.html

Interprofessional Education Collaborative(2022) . IPEC core competencies. Retrieved April 17, 2023 from https://www.ipecollaborative.org/ipec-core-competencies

Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. (2011). Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report on an expert panel. Interprofessional Education Collaborative. https://ipec.memberclicks.net/assets/2011-Original.pdf

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2021). The future of nursing 2020-2030: Charting a path to achieve health equity. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25982

O’Daniel, M., & Rosenstein, A. H. (2011). Professional communication and team collaboration. In: Hughes R.G. (Ed.). Patient safety and quality: An evidence-based handbook for nurses. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); Chapter 33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2637

Rosen, M. A., DiazGranados, D., Dietz, A. S., Benishek, L. E., Thompson, D., Pronovost, P. J., & Weaver, S. J. (2018). Teamwork in healthcare: Key discoveries enabling safer, high-quality care. The American Psychologist, 73(4), 433-450. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000298

The Joint Commission. 2021 Hospital national patient safety goals. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/standards/national-patient-safety-goals/2021/simplified-2021-hap-npsg-goals-final-11420.pdf

Weller, J., Boyd, M., & Cumin, D. (2014). Teams, tribes and patient safety: Overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 90(1061), 149-154. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131168

World Health Organization. (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education & collaborative practice. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/framework-for-action-on-interprofessional-education-collaborative-practice

"1322557028-huge.jpg" by LightField Studios is used under license from Shutterstock.com

"400845937-huge.jpg" by Flamingo Images is used under license from Shutterstock.com

Attribution

Materials in this chapter are attributed to the following sources:

"Leadership and Influencing Change in Nursing" by Joan Wagner Select content adapted for clarity and flow for RN-BSN students is licensed under CC BY 4.0

"Nursing Management and Processional Concepts" by Chippewa Valley Technical College, Modifications: Select content adapted for clarity and flow for RN-BSN students is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Next: 3.20 Leading Effective Change

Learning Objectives

- Identify roles of various health care professionals

- Explore interprofessional communication strategies

- Review team attributes that impact system outcomes

All health care providers must be prepared to work together in clinical practice with a common goal of building a safer, more effective, patient-centered health care system. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines interprofessional collaborative practice as multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds working together with patients, families, caregivers, and communities to deliver the highest quality of care (World Health Organization, 2010).

Effective teamwork and communication have been proven to reduce medical errors, promote a safety culture, and improve patient outcomes (AHRQ, 2015). The importance of effective interprofessional collaboration has become even more important as nurses advocate to reduce health disparities related to social determinants of health (SDOH). In these efforts, nurses work with people from a variety of professions, such as physicians, social workers, educators, policy makers, attorneys, faith leaders, government employees, community advocates, and community members. Nurses must be prepared to effectively collaborate interprofessionally in a variety of health care settings (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2021).

The Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) has identified four core competencies for effective interprofessional collaborative practice. This chapter will review content related to these four core competencies and provide examples of effective teamwork in health systems.

The Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) established standard core competencies for effective interprofessional collaborative practice. The competencies guide the education and practice of health professionals with the necessary knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes to collaboratively work together in providing client care. See Table 3.2 for a description of the four IPEC core competencies (Interprofessional Education Collaborative, n.d.). Each of these competencies will be further discussed in the following sections of this chapter.

Table 3.1 IPEC Core Competencies

| Competency 1: Values/Ethics for Interprofessional Practice

Work with individuals of other professions to maintain a climate of mutual respect and shared values. |

|---|

| Competency 2: Roles/Responsibilities

Use the knowledge of one’s own role and those of other professions to appropriately assess and address the health care needs of patients and to promote and advance the health of populations. |

| Competency 3: Interprofessional Communication

Communicate with patients, families, communities, and professionals in health and other fields in a responsive and responsible manner that supports a team approach to the promotion and maintenance of health and the prevention and treatment of disease. |

| Competency 4: Teams and Teamwork

Apply relationship-building values and the principles of team dynamics to perform effectively in different team roles to plan, deliver, and evaluate patient/population-centered care and population health programs and policies that are safe, timely, efficient, effective, and equitable. |

(Interprofessional Education Collaborative, n.d.)

Next: 3.11 Roles and Responsibilities of Health Care Professionals

IPEC Competency 1: Values/Ethics for Interprofessional Practice

The coordination and delivery of safe, quality patient care demands reliable teamwork and collaboration across the organizational and community boundaries. Clients often have multiple visits across multiple providers working in different organizations. Communication failures between health care settings, departments, and team members is the leading cause of patient harm (Rosen et al., 2018). The health care system is becoming increasingly complex requiring collaboration among diverse health care team members.

The goal of good interprofessional collaboration is improved patient outcomes, as well as increased job satisfaction of health care team professionals. Patients receiving care with poor teamwork are almost five times as likely to experience complications or death. Hospitals in which staff report higher levels of teamwork have lower rates of workplace injuries and illness, fewer incidents of workplace harassment and violence, and lower turnover (Rosen et al., 2018).

Valuing and understanding the roles of team members are important steps toward establishing good interprofessional teamwork. Another step is learning how to effectively communicate with interprofessional team members.

IPEC Competency 2: Roles/Responsibilities

The second IPEC competency relates to the roles and responsibilities of health care professionals and states, “Use the knowledge of one’s own role and those of other professions to appropriately assess and address the health care needs of patients and to promote and advance the health of populations" (Interprofessional Education Collaborative, n.d.).

See the following box for the components of this competency. It is important to understand the roles and responsibilities of the other health care team members; recognize one’s limitations in skills, knowledge, and abilities; and ask for assistance when needed to provide quality, patient-centered care.

Components of IPEC’s Roles/Responsibilities Competency (Interprofessional Education Collaborative, 2022.)

- Communicate one’s roles and responsibilities clearly to patients, families, community members, and other professionals.

- Recognize one’s limitations in skills, knowledge, and abilities.

- Engage with diverse professionals who complement one’s own professional expertise, as well as associated resources, to develop strategies to meet specific health and health care needs of patients and populations.

- Explain the roles and responsibilities of other providers and the manner in which the team works together to provide care, promote health, and prevent disease.

- Use the full scope of knowledge, skills, and abilities of professionals from health and other fields to provide care that is safe, timely, efficient, effective, and equitable.

- Communicate with team members to clarify each member’s responsibility in executing components of a treatment plan or public health intervention.

- Forge interdependent relationships with other professions within and outside of the health system to improve care and advance learning.

- Engage in continuous professional and interprofessional development to enhance team performance and collaboration.

- Use unique and complementary abilities of all members of the team to optimize health and patient care.

- Describe how professionals in health and other fields can collaborate and integrate clinical care and public health interventions to optimize population health.

Nurses communicate with several individuals during their work. For example, during inpatient care, nurses may communicate with patients and their family members; pharmacists and pharmacy technicians; providers from different specialties; physical, speech, and occupational therapists; dietary aides; respiratory therapists; chaplains; social workers; case managers; nursing supervisors, charge nurses, and other staff nurses; assistive personnel; nursing students; nursing instructors; security guards; laboratory personnel; radiology and ultrasound technicians; and surgical team members. Providing holistic, quality, safe, and effective care means every team member taking care of patients must work collaboratively and understand the knowledge, skills, and scope of practice of the other team members. Table 3.4 provides examples of the roles and responsibilities of common health care team members that nurses frequently work with when providing patient care. To fully understand the roles and responsibilities of the multiple members of the complex health care delivery system, it is beneficial to spend time shadowing those within these roles.

Learn more about the roles and responsibilities of individual health care team members by completing the activity below.

Next: 3.12 Interprofessional Communication

IPEC Competency 1: Values/Ethics for Interprofessional Practice

The coordination and delivery of safe, quality patient care demands reliable teamwork and collaboration across the organizational and community boundaries. Clients often have multiple visits across multiple providers working in different organizations. Communication failures between health care settings, departments, and team members is the leading cause of patient harm (Rosen et al., 2018). The health care system is becoming increasingly complex requiring collaboration among diverse health care team members.

The goal of good interprofessional collaboration is improved patient outcomes, as well as increased job satisfaction of health care team professionals. Patients receiving care with poor teamwork are almost five times as likely to experience complications or death. Hospitals in which staff report higher levels of teamwork have lower rates of workplace injuries and illness, fewer incidents of workplace harassment and violence, and lower turnover (Rosen et al., 2018).

Valuing and understanding the roles of team members are important steps toward establishing good interprofessional teamwork. Another step is learning how to effectively communicate with interprofessional team members.

IPEC Competency 2: Roles/Responsibilities

The second IPEC competency relates to the roles and responsibilities of health care professionals and states, “Use the knowledge of one’s own role and those of other professions to appropriately assess and address the health care needs of patients and to promote and advance the health of populations" (Interprofessional Education Collaborative, n.d.).

See the following box for the components of this competency. It is important to understand the roles and responsibilities of the other health care team members; recognize one’s limitations in skills, knowledge, and abilities; and ask for assistance when needed to provide quality, patient-centered care.

Components of IPEC’s Roles/Responsibilities Competency (Interprofessional Education Collaborative, 2022.)

- Communicate one’s roles and responsibilities clearly to patients, families, community members, and other professionals.

- Recognize one’s limitations in skills, knowledge, and abilities.

- Engage with diverse professionals who complement one’s own professional expertise, as well as associated resources, to develop strategies to meet specific health and health care needs of patients and populations.

- Explain the roles and responsibilities of other providers and the manner in which the team works together to provide care, promote health, and prevent disease.

- Use the full scope of knowledge, skills, and abilities of professionals from health and other fields to provide care that is safe, timely, efficient, effective, and equitable.

- Communicate with team members to clarify each member’s responsibility in executing components of a treatment plan or public health intervention.

- Forge interdependent relationships with other professions within and outside of the health system to improve care and advance learning.

- Engage in continuous professional and interprofessional development to enhance team performance and collaboration.

- Use unique and complementary abilities of all members of the team to optimize health and patient care.

- Describe how professionals in health and other fields can collaborate and integrate clinical care and public health interventions to optimize population health.

Nurses communicate with several individuals during their work. For example, during inpatient care, nurses may communicate with patients and their family members; pharmacists and pharmacy technicians; providers from different specialties; physical, speech, and occupational therapists; dietary aides; respiratory therapists; chaplains; social workers; case managers; nursing supervisors, charge nurses, and other staff nurses; assistive personnel; nursing students; nursing instructors; security guards; laboratory personnel; radiology and ultrasound technicians; and surgical team members. Providing holistic, quality, safe, and effective care means every team member taking care of patients must work collaboratively and understand the knowledge, skills, and scope of practice of the other team members. Table 3.4 provides examples of the roles and responsibilities of common health care team members that nurses frequently work with when providing patient care. To fully understand the roles and responsibilities of the multiple members of the complex health care delivery system, it is beneficial to spend time shadowing those within these roles.

Learn more about the roles and responsibilities of individual health care team members by completing the activity below.

Next: 3.12 Interprofessional Communication

Jamie normally works the overnight shift on a general medical floor and was floated to an orthopedic unit for the night shift due to increased patient census on that unit. Jamie has worked for the organization for 15 years and was working with four new RNs that recently completed orientation on the orthopedic unit. Jamie was assigned to be the charge nurse on this unit for this shift. Jamie was not happy about this assignment and was concerned about adequate staffing. In addition to the other 4 RNs, the patient care team for the night shift included 3 patient-care technicians (PCT) . One was newly hired in the health system and still orientating, but the other PCTs had worked on this unit for over 5 years.

Jamie focused on creating an effective team and ensuring effective communication. A few hours into the shift, Jamie noticed that one of the RNs was delegating patient care tasks that were outside the scope of practice for the PCT and should not be delegated by the RN. When Jamie asked the RN and PCT about this delegation, PCT had been doing this for “years” and had indicated that they were always trusted to perform these particular tasks.

Next: 3.15 References & Attribution

IPEC Competency 3: Interprofessional Communication

The third IPEC competency focuses on interprofessional communication and states, “Communicate with patients, families, communities, and professionals in health and other fields in a responsive and responsible manner that supports a team approach to the promotion and maintenance of health and the prevention and treatment of disease” (Interprofessional Education Collaborative, 2022.). This competency also aligns with The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goal for improving staff communication (The Joint Commission, 2021). See the following box for the components associated with the Interprofessional Communication competency.

Components of IPEC’s Interprofessional Communication Competency (Interprofessional Education Collaborative, 2022)

- Choose effective communication tools and techniques, including information systems and communication technologies, to facilitate discussions and interactions that enhance team function.

- Communicate information with patients, families, community members, and health team members in a form that is understandable, avoiding discipline-specific terminology when possible.

- Express one’s knowledge and opinions to team members involved in patient care and population health improvement with confidence, clarity, and respect, working to ensure common understanding of information, treatment, care decisions, and population health programs and policies.

- Listen actively and encourage ideas and opinions of other team members.

- Give timely, sensitive, constructive feedback to others about their performance on the team, responding respectfully as a team member to feedback from others.

- Use respectful language appropriate for a given difficult situation, crucial conversation, or conflict.

- Recognize how one’s uniqueness (experience level, expertise, culture, power, and hierarchy within the health care team) contributes to effective communication, conflict resolution, and positive interprofessional working relationships.

- Communicate the importance of teamwork in patient-centered care and population health programs and policies.

Transmission of information among members of the health care team and facilities is ongoing and critical to quality care. However, information that is delayed, inefficient, or inadequate creates barriers for providing quality of care. Communication barriers continue to exist in health care environments due to interprofessional team members’ lack of experience when interacting with other disciplines. For instance, many novice nurses enter the workforce without experiencing communication with other members of the health care team (e.g., providers, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, social workers, surgical staff, dieticians, physical therapists, etc.). Additionally, health care professionals tend to develop a professional identity based on their educational program with a distinction made between groups. This distinction can cause tension between professional groups due to diverse training and perspectives on providing quality patient care. In addition, a health care organization’s environment may not be conducive to effectively sharing information with multiple staff members across multiple units.

In addition to potential educational, psychological, and organizational barriers to sharing information, there can also be general barriers that impact interprofessional communication and collaboration. See the following box for a list of these general barriers (O'Daniel & Rosenstein, 2011).

General Barriers to Interprofessional Communication and Collaboration (O'Daniel & Rosenstein, 2011)

- Personal values and expectations

- Personality differences

- Organizational hierarchy

- Lack of cultural humility

- Generational differences

- Historical interprofessional and intraprofessional rivalries

- Differences in language and medical jargon

- Differences in schedules and professional routines

- Varying levels of preparation, qualifications, and status

- Differences in requirements, regulations, and norms of professional education

- Fears of diluted professional identity

- Differences in accountability and reimbursement models

- Diverse clinical responsibilities

- Increased complexity of patient care

- Emphasis on rapid decision-making

There are several national initiatives that have been developed to overcome barriers to communication among interprofessional team members. These initiatives are summarized in Table 3.2 (Weller et al., 2014).

Table 3.2 Initiatives to Overcome Barriers to Interprofessional Communication and Collaboration (Weller et al., 2014)

| Action | Description |

|---|---|

| Teach structured interprofessional communication strategies | Structured communication strategies, such as ISBARR, handoff reports, I-PASS reports, and closed-loop communication should be taught to all health professionals. |

| Train interprofessional teams together | Teams that work together should train together. |

| Train teams using simulation | Simulation creates a safe environment to practice communication strategies and increase interdisciplinary understanding. |

| Define cohesive interprofessional teams | Interprofessional health care teams should be defined within organizations as a cohesive whole with common goals and not just a collection of disciplines. |

| Create democratic teams | All members of the health care team should feel valued. Creating democratic teams (instead of establishing hierarchies) encourages open team communication. |

| Support teamwork with protocols and procedures | Protocols and procedures encouraging information sharing across the whole team include checklists, briefings, huddles, and debriefing. Technology and informatics should also be used to promote information sharing among team members. |

| Develop an organizational culture supporting health care teams | Agency leaders must establish a safety culture and emphasize the importance of effective interprofessional collaboration for achieving good patient outcomes. |

Communication Strategies

Several communication strategies have been implemented nationally to ensure information is exchanged among health care team members in a structured, concise, and accurate manner to promote safe patient care. Examples of these initiatives are ISBARR, handoff reports, closed-loop communication, and I-PASS. Documentation that promotes sharing information interprofessionally to promote continuity of care is also essential. These strategies are reviewed in Appendix C.

Nurses may already be using these strategies in their health system. However, a key responsibility of nursing leaders is to ensure that communication tools are used effectively. Nurses are encouraged to review the barriers and strategies to determine the efficacy of communication within their own health system. Assessing one's own communication style is helpful in identifying potential strategies for enhanced communication. See Applied Learning Activity 3.2 Communication Style Inventory below.

Applied Learning Activity 3.2 Communication Style Inventory

Next: 3.13 Teams and Teamwork

Appendix C

IPEC Competency 4: Teams and Teamwork

Now that we have reviewed the first three IPEC competencies related to valuing team members , understanding team members’ roles and responsibilities and interprofessional communication, let’s discuss strategies that promote effective teamwork. The fourth IPEC competency states, “Apply relationship-building values and the principles of team dynamics to perform effectively in different team roles to plan, deliver, and evaluate patient/population-centered care and population health programs and policies that are safe, timely, efficient, effective, and equitable” (Interprofessional Education Collaborative, n.d.). See the following box for the components of this IPEC competency.

Components of IPEC’s Teams and Teamwork Competency (Interprofessional Education Collaborative, 2022.)

- Describe the process of team development and the roles and practices of effective teams.

- Develop consensus on the ethical principles to guide all aspects of teamwork.

- Engage health and other professionals in shared patient-centered and population-focused problem-solving.

- Integrate the knowledge and experience of health and other professions to inform health and care decisions, while respecting patient and community values and priorities/preferences for care.

- Apply leadership practices that support collaborative practice and team effectiveness.

- Engage self and others to constructively manage disagreements about values, roles, goals, and actions that arise among health and other professionals and with patients, families, and community members.

- Share accountability with other professions, patients, and communities for outcomes relevant to prevention and health care.

- Reflect on individual and team performance for individual, as well as team, performance improvement.

- Use process improvement to increase effectiveness of interprofessional teamwork and team-based services, programs, and policies.

- Use available evidence to inform effective teamwork and team-based practices.

- Perform effectively on teams and in different team roles in a variety of settings.

Developing effective teams is critical for providing health care that is patient-centered, safe, timely, effective, efficient, and equitable (Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel, 2011).

Nurses collaborate with the interprofessional team by not only assigning and coordinating tasks, but also by promoting solid teamwork in a positive environment. A nursing leader, such as a charge nurse, identifies gaps in workflow, recognizes when task overload is occurring, and promotes the adaptability of the team to respond to evolving patient conditions. Qualities of a successful team are described in the following box (O'Daniel & Rosenstein, 2011).

Qualities of A Successful Team (O'Daniel & Rosenstein, 2011)

- Promote a respectful atmosphere

- Define clear roles and responsibilities for team members

- Regularly and routinely share information

- Encourage open communication

- Implement a culture of safety

- Provide clear directions

- Share responsibility for team success

- Balance team member participation based on the current situation

- Acknowledge and manage conflict

- Enforce accountability among all team members

- Communicate the decision-making process

- Facilitate access to needed resources

- Evaluate team outcomes and adjust as needed

STEP Tool

STEP is a tool for monitoring the delivery of health care

STEP Tool (AHRQ, 2020)

Status of Patients: “What is going on with your patients?”

- Patient History

- Vital Signs

- Medications

- Physical Exam

- Plan of Care

- Psychosocial Issues

Team Members: “What is going on with you and your team?”(See the “I’M SAFE Checklist” below.)

- Fatigue

- Workload

- Task Performance

- Skill

- Stress

Environment: Knowing Your Resources

- Facility Information

- Administrative Information

- Human Resources

- Triage Acuity

- Equipment

Progression Towards Goal:

- Status of the Team's Patients

- Established Goals of the Team

- Tasks/Actions of the Team

- Appropriateness of the Plan - Are Modifications Needed?

Cross Monitoring

As the STEP tool is implemented, the team leader continues to cross monitor to reduce the incidence of errors. Cross monitoring includes the following (AHRQ, 2020):

- Monitoring the actions of other team members.

- Providing a safety net within the team.

- Ensuring that mistakes or oversights are caught quickly and easily.

- Supporting each other as needed.

I’M SAFE Checklist

The I’M SAFE mnemonic is a tool used to assess one’s own safety status, as well as that of other team members in their ability to provide safe patient care. See the I’M SAFE Checklist in the following box (AHRQ, 2020). If a team member feels their ability to provide safe care is diminished because of one of these factors, they should notify the charge nurse or other nursing supervisor. In a similar manner, if a nurse notices that another member of the team is impaired or providing care in an unsafe manner, it is an ethical imperative to protect clients and report their concerns according to agency policy (AHRQ, 2020).

I'm SAFE Checklist (AHRQ, 2020)

- I: Illness

- M: Medication

- S: Stress

- A: Alcohol and Drugs

- F: Fatigue

- E: Eating and Elimination

Read an example of a nursing team leader performing situation monitoring using the STEP tool in the following box.

Example of Situation Monitoring

Two emergent situations occur simultaneously on a busy medical-surgical hospital unit as one patient codes and another develops a postoperative hemorrhage. Connie, the charge nurse, is performing situation monitoring by continually scanning and assessing the status of all patients on the unit and directing additional assistance where it is needed. Each nursing team member maintains situation awareness by being aware of what is happening on the unit, in addition to caring for the patients they have been assigned. Connie creates a shared mental model by ensuring all team members are aware of their evolving responsibilities as the situation changes.

Connie directs additional assistance to the emergent patients while also ensuring appropriate coverage for the other patients on the unit to ensure all patients receive safe and effective care. For example, as the “code” is called, Connie directs two additional nurses and two additional assistive personnel to assist with the emergent patients while the other nurses and assistive personnel are directed to “cover” the remaining patients, answer call lights, and assist patients to the bathroom to prevent falls. Additionally, Connie is aware that after performing a few rounds of CPR for the coding patient, the assistive personnel must be switched with another team member to maintain effective chest compressions. As the situation progresses, Connie evaluates the status of all patients and makes adjustments to the plan as needed.

Mutual Support

Mutual support is the fourth skill of the TeamSTEPPS® framework and defined as the “ability to anticipate and support team members' needs through accurate knowledge about their responsibilities and workload” (AHRQ, 2020). Mutual support includes providing task assistance, giving feedback, and advocating for patient safety by using assertive statements to correct a safety concern. Managing conflict is also a component of supporting team members’ needs.

Task Assistance

Helping other team members with tasks builds a strong team. Task assistance includes the following components (AHRQ, 2020):

- Team members protect each other from work-overload situations.

- Effective teams place all offers and requests for assistance in the context of patient safety.

- Team members foster a climate where it is expected that assistance will be actively sought and offered.

Example of Task Assistance

In the previous example, one patient on the unit was coding while another was experiencing a postoperative hemorrhage. After the emergent care was provided and the hemorrhaging patient was stabilized, Sue, the nurse caring for the hemorrhaging patient, finds many scheduled medications for her other patients are past due. Sue reaches out to Sam, another nurse on the team, and requests assistance. Sam agrees to administer a scheduled IV antibiotic to a stable third patient so Sue can administer oral medications to her remaining patients. Sam knows that on an upcoming shift, he may need to request assistance from Sue when unexpected situations occur. In this manner, team members foster a climate where assistance is actively sought and offered to maintain patient safety.

Feedback

Feedback is provided to a team member for the purpose of improving team performance. Effective feedback should follow these parameters (AHRQ, 2020):

- Timely: Provided soon after the target behavior has occurred.

- Respectful: Focused on behaviors, not personal attributes.

- Specific: Related to a specific task or behavior that requires correction or improvement.

- Directed towards improvement: Suggestions are made for future improvement.

- Considerate: Team members’ feelings should be considered and privacy provided. Negative information should be delivered with fairness and respect

Strategies for effective communication are found in Appendix C.